by: Hobart Taylor

by: Hobart Taylor

As I write this today July 17th 2018 is the fifty first anniversary of the passing of John Coltrane. Often "passing" is a euphemism for dying, but occasionally it is an accurate description of the transition from the corporeal to the spiritual state, and I don't mean New Jersey.

Everything that follows here is a meditation on my personal experience with the music of John Coltrane, and what I believe it means.

Here is the official disclaimer: I am not a jazz scholar or musician. My experience as a human, an African-American, a jazz radio programmer, a writer, and intense listener fill the well I am dipping from.

Recently two new recordings have brought Coltrane back into the forefront of the American cultural conversation. The first one was the latest in the release of concert bootlegs featuring the brief collaboration between Coltrane and Miles Davis, The Final Tour Vol. 6 which was recently reviewed here

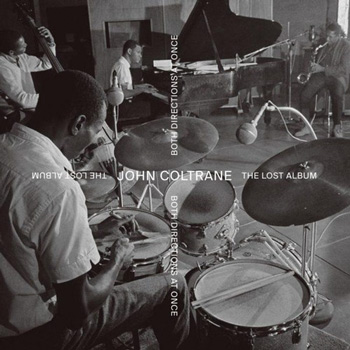

The second was a 1963 studio album which was previously unreleased, Both Directions At Once: The Lost Album.

I am not going to review that record here. Just get it.

It is popular to build a myth around artists that obscures their embodiment. Coltrane walked, talked, spat, and shat. He felt, smelt, cried and lied. I never met him, saw him, or met anyone close to him. The intimate connection I sense to what I call John Coltrane is entirely a work of imagination driven by neurological responses and subsequent reflections.

Through the music he and his collaborators created there emerges constantly for me a Coltrane spirit. That is what I mean from here on out when I refer to Coltrane.

That spirit utters a cry to transcend categorization by race, gender, class, nationality, or genre, by summoning up the divine. When that occurs authentically people call it genius.

For me it is essential to recognize that Coltrane's greatest creativity coincided with the process of humanization for African-Americans, colloquially called the civil rights movement.

Implicit in his music and performance were African-American, African, and other non-European influences that easily co-existed with the "norms", pop music and Euro-American melodic convention. In other words, his music was integrated. He was not alone in doing this, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and a long list of other folks followed suit.

What is special about Coltrane is the level of spiritual commitment to using whatever tools were handy, melodies, harmonic structures, rhythms, players, compositional acumen, moods and sensibilities, to evoke the supreme.

And people got it. Black people got it. White people got it. Pop music fans got it. Intellectuals got it. Coltrane moved the needle. He was not a great black artist. He was a great artist who was black. That's liberation. That's Coltrane. That's why his music continues to matter through time.

Share

|

|